In our current era where almost anything can be Googled or bought on Amazon or Ebay, the vital role that record stores played in the 60s and 70s might be hard to grasp. For those of us living down on the Midpeninsula, such stores played a vital role beyond just selling records, by serving as an information pipeline to what was occurring in the fast evolving rock world in San Francisco, other American cities, and the UK. Because most regular newpapers (Ralph Gleason’s postings in the San Francisco Chronicle being a notable exception) did not mention anything beyond the biggest musical events, the bulletin boards in these stores, and the knowledge of their staff, were vital sources of information for what was going on in the local music communitiy.

The Midpeninsula had an abundance of stores, each with their own distinctive character. One big difference had to do with who got things first. For at least the last decade, the mainstream music industry has decreed that all ‘product’ will be released on Tuesdays. In the sixties, records could come out any day of the week (well, maybe not Saturday or Sunday), and it was certainly true that not all stores got new releases on the same day. I remember having a bunch of new friends for a day back in December 1968 when I got a copy of the Beatles White Album a day or two before it was in most stores because the record store at Mayfield Mall somehow got a stack of copies before everyone else. I developed a routine of dropping into various of the area stores a few times a week, either riding there on my bicycle or grabbing a ride with family members of driving age.

a day or two before it was in most stores because the record store at Mayfield Mall somehow got a stack of copies before everyone else. I developed a routine of dropping into various of the area stores a few times a week, either riding there on my bicycle or grabbing a ride with family members of driving age.

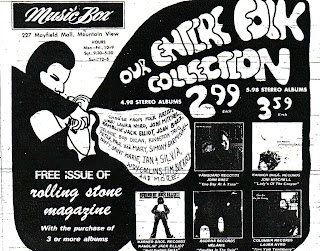

The Music Box at Mayfield Mall was not that terribly different than the Mall stores of the last couple of decades with the exception that they sold vinyl records instead of CDs. They had a nice selection of cut-out records that would sell for $1.00 or less, and I did find some interesting things there, including the aforementioned Beatles early release and one of the few copies I ever saw in a store of the original Grateful Dead single version of “Dark Star”/”Born Crosseyed.”

Mayfield Mall was an interesting institution. One of the very first indoor malls, its advantage to me was a short, easy commute from home or school. You can read about its history here. It was converted to a Hewlett Packard facility in 1984.

A bit further away (and requiring a somewhat perilous transit over the Central Expressway/San Antonio overpass) was San Antonio Music, located in the San Antonio Shopping Center. I remember this store as having more knowlegable employees, and almost always having new releases on sale. I remember vividly riding over there in the summer of 1968 and snapping up a copy of the garishly foil covered Cream album Wheels of Fire , which was one of the earliest double LP releases by a rock act, for six bucks the day it came out. The music store is long gone, but the San Antonio Shopping Center remains, albeit seriously mutated from its mid-60s configuration. Gone are such icons as the iconic Menu Tree food court, which was two stories and featured a bunch of singing animated bird, and the San Antonio Hobby Shop, which started out in a small storefront on the eastern strip that also contained Thrifty and Woolworth’s and expanded to become one of the largest such stores in the country. Today all of these are long gone, and the center features such franchises as a 24 Hour Fitness, a Trader Joe’s, and a Walmart. Incredibly, the 60s vintage Sears store remains its centerpiece, although it also nearly closed a few years ago.

, which was one of the earliest double LP releases by a rock act, for six bucks the day it came out. The music store is long gone, but the San Antonio Shopping Center remains, albeit seriously mutated from its mid-60s configuration. Gone are such icons as the iconic Menu Tree food court, which was two stories and featured a bunch of singing animated bird, and the San Antonio Hobby Shop, which started out in a small storefront on the eastern strip that also contained Thrifty and Woolworth’s and expanded to become one of the largest such stores in the country. Today all of these are long gone, and the center features such franchises as a 24 Hour Fitness, a Trader Joe’s, and a Walmart. Incredibly, the 60s vintage Sears store remains its centerpiece, although it also nearly closed a few years ago.

Going northward from home, another regular stop was Town and Country Music, located near the back of Town and Country Village where the Day One baby supply store is located now. This was kind of a mom and pop operation, as I remember, but they did have a good selection as well as good prices. As a link to a still earlier era, they retained listening booths with turntables and headphones long after this user-friendly convention disappeared from the music sales culture. Of course, in today’s version of this, you can generally scan a CD’s bar code and listen to mp3s at a listening station at your neighborhood Border’s or check out samples online. Although the music store, again, is gone, Town and Country remains a thriving destination, little changed physically from its 1960s form.

The area’s best record store was arguably Menlo Park’s Discount Records, on El Camino Real just across Live Oak Avenue from the original location of Kepler’s Books. Discount Records was a small chain, but the Menlo store didn’t have anything like a corporate feel. Years before I began collecting records myself, this was a regular stop on the Saturday rounds I would take with my dad and sometimes my brother. Like Kepler’s, Discount Records was a place where hanging out was encouraged, and it would be common for us to be there for at least an hour while he pored over their always impressive stock of jazz records. It’s pretty easy to see where my own habits developed, and I became like the proverbial kid in a candy store once I got started. The staff there always knew their music well, and generally played really interesting records on their top-quality sound system.

As the rock era dawned, Discount Records was right there. They sold tickets to the Fillmore and other venues, and would receive a shipment of the small handbill sized reproductions of the Fillmore posters every Tuesday afternoon, which I made a point of picking up whenever possible. They also tended to have posters advertising regional events, and it was there that I learned about the 1970 and 1971 appearances at nearby Peninsula School by the New Riders of the Purple Sage that I will get to in a future post.

Another big asset the store had was a large selection of British Import LPs. In the 60s and 70s, British versions of LPs were generally pressed on thicker, higher quality vinyl and had sleeves made of a different, shinier formulation of cardboard. Many British albums were never released in the US (the two volumes of Diary of a Band by John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers comes to mind), and they often came out in the UK months before they were released in the US, like the first two albums by Traffic

by John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers comes to mind), and they often came out in the UK months before they were released in the US, like the first two albums by Traffic . When a British act did release an album in the US, it was often drastically different in sequence and content than the UK version, a phenomenon best exemplified by the UK vs. US versions of the pre-Sergeant Pepper Beatles albums.

. When a British act did release an album in the US, it was often drastically different in sequence and content than the UK version, a phenomenon best exemplified by the UK vs. US versions of the pre-Sergeant Pepper Beatles albums.

In 1970, what became my favorite area record store opened in Downtown Palo Alto. World’s Indoor Records established itself in part of a Victorian that still stands at the corner of Kipling Street and Lytton Avenue. WIR was a small, funky, one-person shop, owned by a friendly red headed dude named Roy. His avuncular, laid back manner, and his encyclopedic knowledge of the new music coming out, made it a great place to hang out, listen to, and buy music. The single big room was cozy, and stuffed with interesting records. Somehow he always seemed to come up with things that weren’t available elsewhere (like the original, super rare Glastonbury Fayre 3 LP set that came out in 1972), and he was also a passionate advocate (and canny salesperson) for obscure records. I remember him putting on the debut album by Jesse Winchester

3 LP set that came out in 1972), and he was also a passionate advocate (and canny salesperson) for obscure records. I remember him putting on the debut album by Jesse Winchester , then essentially unknown in the states, pointing out the production and engineering credits by Robbie Robertson and Todd Rundgren, respectively, and the few of us in the store being simply awestruck by the quiet glory of that magnificent, timeless record. He was also service oriented. I recall him actually trying to talk me out of buying Captain Beefheart’s Trout Mask Replica

, then essentially unknown in the states, pointing out the production and engineering credits by Robbie Robertson and Todd Rundgren, respectively, and the few of us in the store being simply awestruck by the quiet glory of that magnificent, timeless record. He was also service oriented. I recall him actually trying to talk me out of buying Captain Beefheart’s Trout Mask Replica , and even offering to take it back if I hated it (I kept it, of course).

, and even offering to take it back if I hated it (I kept it, of course).

In short order, World’s Indoor Records was joined in the Victorian by Chimera, which sold used books and used records. While used records and CDs are a common coin of the realm today, stores that sold them were still relatively rare as the seventies dawned, and Chimera, like its retail housemate, seemed to attract some of the best and most obscure recordings, most of which could be bought for around $2.00 at the time. Starting with a single room downstairs, Chimaera’s mostly literary holdings ultimately sprawled through the rest of the downstairs and all of the upstairs of the house, and ultimately outlived World’s Indoor Records, which closed sometime in the late 1970s. Today the Victorian is broken up into apartments. Chimaera moved onto University Avenue for many years, and is now up on Middlefield Road in Redwood City.

A final oddity worth mentioning is Banana Records, which appeared in the late '60s on El Camino Real south of California Avenue. It had a reasonable, but not outstanding selection, but was notable because it was housed in a wooden cube resembling a record crate. The building remains, just a few doors down from the Palo Alto Fry's and it currently houses an Ipod repair facility.

Up in the city, the ultimate record destination in this era was the Tower Records store at Columbus and Bay Streets, perched between North Beach and Fisherman’s Wharf. Long before it became an international franchise, there were three Tower locations, the initial store in Sacramento, the San Francisco store, and one on the Sunset Strip in Los Angeles. In this pre-Amazon era, Tower was legendary among the music community for having the greatest selection of records. It was not at all uncommon to find both local and touring musicians browsing through the vast converted grocery store. Tower also initiated the giant painted murals of album covers that adorned the exterior of the San Francisco and Los Angeles stores. Sadly, the entire Tower chain was sold and liquidated in 2006.

Before I wrap this up, a couple of other regional nods. I first experienced the treasure trove that was (and is) Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley when one of the first bootleg records, Liver than You’ll Ever Be, came on the market in late 1969. At that point, the only place to buy it was Leopold’s, which at that time was in a small storefront in the mall on the north side of Durant on the block east of Telegraph, just across the street from where its much larger location ended up for a couple of decades until it closed several years back. During my college years and thereafter, Telegraph was the place to shop for used records, with the prime locations being the basement of Moe’s Books, which stopped selling records probably 30 years ago, and the original tiny location of the first Rasputin’s on the west side of the first block of Telegraph. Rasputin’s sprawled and has spawned a number of rather uninspired locations throughout the bay area, but the Berkeley location, particularly its roomy basement, still yields up some cool stuff.

In 1990, Amoeba records opened a bit further down Telegraph, and it quickly became and has remained the destination of choice for those of us that still buy records and/or CDs. Easily as big as the original San Francisco Tower, Amoeba has immense collections of virtually every genre of music, well organized and nicely displayed. The other two stores in the chain, on Haight Street in San Francisco and on Sunset in Hollywood, are even bigger, but the Berkeley store is still the best of the lot in my book.

The time warp award goes to Logos on Pacific Avenue in Santa Cruz. When I moved to Santa Cruz for college in 1971, it was in a small shop on Cooper Street, just opposite the Cooper House. In short order, it moved to a location on Pacific proper a couple of blocks down the street. The building housing Logos was leveled after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, but it rose like a phoenix into its current two story location between Cathcart and Lincoln Streets, kitty corner from the Del Mar Theatre. Even before vinyl became cool again, they had a massive collection of vinyl that, I would swear, contained the same copies of Moby Grape and Doobie Brothers albums that they were selling back in the seventies. Their prices have risen recently in keeping with the resurgence of vinyl collecting, but they still have an amazing assortment of albums.